On criticizing coaching

You have to be considerate of the unseen factors guiding coaching decisions.

Given a decade of writing about football’s tactics and the back and forth battles between coaches, you’ll tend to offer some critical remarks at some point or another. What are any of us blogboyz in this for but to critique and armchair quarterback the big games?

As a graduate of the University of Texas and a regular commenter on their football program over that period, of course I’ve uttered or written innumerable complaints or issues with how they’ve approached the task of winning football games.

At various points, I’ve met very fierce resistance to the the very notion of criticizing coaching decisions from an internet column, particularly from coaches. I heard from one particular coach who thought coaching decisions had too many behind the scenes details to be criticized by any outsider, particularly one who wasn’t a coach.

His opinion didn’t quite stick with me. If you believe in democracy and the right of all Americans to deeply criticize the decision-making of their President and elected officials who have access to information and considerations many of us couldn’t fathom (and he did), then the right of a paying fan or media member to question why the coach called ineffective plays appears to be well-founded.

The perspective of a criticized coach resonated with me more though when I had the chance to chat with a former coach at the University of Texas. Hearing how critical commentaries from silly bloggers like myself had landed with impact in the workings of the team was a bit jarring. The coach outlined issues and battles he was facing within the program which were a level beyond anything I had taken into consideration when questioning the secondary’s positioning against a running quarterback. It was more sobering than the other coach’s broad and seemingly self-serving admonishments and lead me to question how blasé I should be about offering serious criticisms from a keyboard.

What you’ll often hear from coaches who dislike the very notion of receiving criticism from the media, or from fans who are protective of particular coaches or players, is handwaving toward vague issues which can complicate the process in getting 18-23 year old young men to execute a task in cohesion. Relational dynamics, politics with coaches, boosters, or player’s parents, recruiting concerns, team dynamics, the list of potential complicating factors goes on and on.

It’s often rather vague and necessarily so, but the defensive refrain will tend to go something like, “have you ever coached? Have you ever even managed a team of people? No, you’re just flying solo and writing safely from a basement.”

Well, actually I do and have, and it has indeed given me a tremendous insight and understanding of the potential complications in leading a team.

My second life as a “coach”

For most of my time as a sportswriter, I’ve had a second part-time job virtually none of my readers know anything about. I’m a worship pastor at a small local church in southeast Michigan.

Indeed, taking on that job is the reason why I am a Michigan resident despite having family, alma mater, friends, and business interests back in the state of Texas.

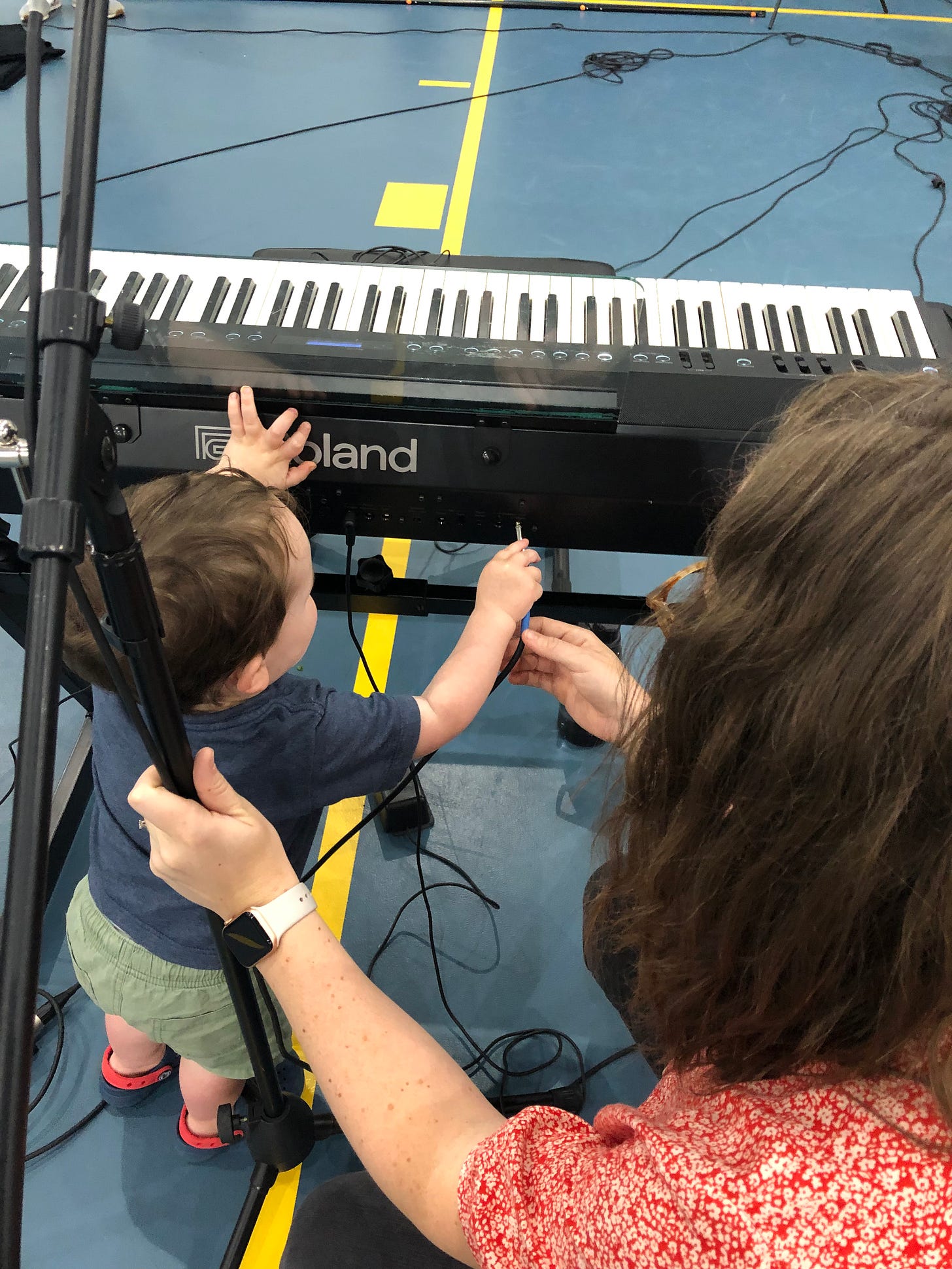

“Worship pastor at a small local church” means a lot of things, if you’re entirely unfamiliar with that term. On the most basic level it means that I organize a band every Sunday and direct them (as one of the component parts) in singing 3-6 songs (it’s varied over the years) at various parts of our service. I lead with my wife, who’s the real musical talent between the two of us, but I’m the one who picks the songs, picks the band, directs practices (every Thursday night), and calls most of the shots.

I’m the coach, basically.

It’s a tough gig at times. We’re a small church so we rely on volunteers to man most of the duties that go into making services happen. The nature of a musical band tends to draw people who are often one or more of the following:

Opinionatedly creative.

Interested in being in the spotlight.

Vulnerable either in “performing” for others in the first place or in doing so as a part of a process they can’t directly control.

Creative people love to be “unique,” they often hate anything that feels like appealing to a lowest common denominator. Many are insecure yet passionate about performing deep and emotional expressions of art and worship in front of other people and particularly in doing so under someone else’s direction or oversight.

As the worship pastor, I have to serve four different masters. They include, in no particular order:

My own sense of how to obey and honor the Lord in my job.

The vision of the local church leadership.

The needs of the congregation.

The particular needs of the actual worship band.

Balancing those can be tricky and I’m often calling upon my tendency to be “contrar-Ian” in doing so.

For instance, “sure lead pastor, that new Hillsong track is great but we don’t have two drum kits and three electric guitars. It’s me on guitar, a guy on cajon who just joined the band, and it looks like my wife is going to have to play the keys. So…we’re a bit limited.”

Or alternatively, “hey guys, I know we’ve sung this song a million times and we’re a little bored with it, but it’s easy for us to do well, people respond when we sing it, and it’s hard to find upbeat songs we can replicate with a smaller band.”

I’m always balancing creative inputs from other people, the needs of the church and the vision of a particular service, and the importance of guiding and protecting a volunteer band who are giving up their free time to try and engage in expressive and vulnerable art in front of other people.

It can add up.

At one point in my time as the worship pastor, a brilliant leader from within the broader network my church is in came and did some equipping on leadership styles. In a meeting I had with him he outlined processes and styles of collaborative and servant leadership, many of which I’d already learned to employ. As he laid out some of the different principles, I realized much of what I believe about leadership I learned in part from reading “Watership down” as a kid.

I tried to mention it but…if the other person hasn’t read it, you sound silly in a hurry if you try to talk about learning leadership skills from a book about rabbits on an adventure. I did later look up some details and discovered the “Hazel” character and much of the story was inspired by author Richard Adams’ experience in World War II under a British officer he’s described as the greatest natural leader he’d ever known. The hallmarks of Hazel’s leadership in the book, and I suppose of this officer, include collaborative leadership mixed with sacrifice and particular risk-taking on the part of the leader.

Making decisions? Everyone gets to be a part. Owning the consequences of a decision or the risks in executing it? Those go to the leader when possible.

Balancing different concerns, goals, and actual people is a challenge. It’s hilarious to imagine if there were blogs written about our weekly performances as a worship team wherein I get to take the sorts of public lumps coaches are regularly dealt.

Coaching people is hard

One complaint I routinely see levied at coaches I’ve become particularly unsympathetic toward is the “why didn’t you play the star rookie/freshman sooner?”

Mack Brown was famously lambasted for not playing freshman running back Cedric Benson during the 2001 season until AFTER the offense had been absolutely crushed in 14-3 loss to the rival Oklahoma Sooners in the Red River Shootout.

His reasoning, “well, he didn’t know our pass protections yet.”

How many times have you heard that complaint about a young running back who doesn’t see the field regularly?

The typical fan might retort:

He’s your best player! It’s your job to teach him what he needs to know to see the field or else to adjust the offense so it’s not a problem!

Put him on the field at times when you don’t need him to protect the quarterback!

Well we lost the game when we didn’t block Roy Williams on a safety blitz so you might as well have played him!

All reasonable, but they all point to a sinister problem facing the head coach. If you develop a clearly talented player and then put them on the field, you’ll immediately invite critiques about why their talent wasn’t seen earlier, particularly if you’re losing.

I’ve had a number of supremely talented people serve with me on the worship team, often with singing or instrumentation talent that clearly exceeds my own. As a “player coach” I’ve faced a couple of challenges in incorporating their abilities within the team/band concept.

One challenge is that I routinely “must decrease so they can increase.” I’ve been aided in that sacrificial journey by having to understand my full-time role within the team as essentially playing point guard, often for my own wife who’s the brilliant scoring forward who can dominate games on offense if the rest of us will just play our roles. Once you accept that role for one teammate, it’s not as hard to do so for others.

The other is in slowly bringing people along and entrusting authority and opportunities to talented people by inviting them into the planning process. Because our overall project as a worship team is ultimately about serving the congregation and doing so within the bounds of the church’s vision and the needs and abilities of our bandmates, it doesn’t really do to immediately stick a talented person front and center or give them a ton of control or leeway. It’s better if they understand the vision, have demonstrated they can play well with teammates, and have the appropriate “servant leadership” mindset so they don’t just grab the mic and yell “Kobe!”

I’ve heard coaches insist on the classic “hey look, I know they were awesome when they saw the field, but believe me they weren’t ready to do that before they did…” It sounds very convenient, yet I’ve seen it with my own eyes as well.

I had a member of the band once who needed a little coaching and encouragement before they fully found their singing voice (at least in our context). She was actually showing me a song she wanted to try and lead on a Sunday and was singing it in her characteristically low, quiet tones.

‘That’s cool! Ummm, can you take it up a key and sing it a little higher?”

“Yeah, that’s interesting. How about up one more key?”

“Uh huh, one more.”

Next thing I know she’s belting out these beautiful notes with some power we haven’t heard from her before. In one sense it’s a bit of a relief to look back and know I wasn’t the one holding her back, I helped her grow in confidence. On the other hand, it took a while before I knew how to help her unlock the talent.

If there’d been someone gauging our worship band’s performances in a weekly column who felt we’d been underachieving, they would have had a field day with what happened next. We gave this young woman increasing numbers of opportunities to help pick and lead songs and she was an outstanding vocalist and leader, to the great benefit of the church.

“She should have been singing more this whole time! She should be in charge of the whole band rather than this joker who can’t sing or play half as well as she can!”

She probably could be in charge and do a better job than me eventually, but she wasn’t the star others saw until she was.

The world of analytics offers the most unforgiving variety of this analysis. You can argue until you’re blue in the face but the numbers will say what they say.

It’s particularly amusing to imagine someone using some sort of analytics system to judge a worship team.

“The band doesn’t play nearly enough Bethel songs. The number of congregationalists who raise their hands in worship is 30% higher when the band plays Bethel songs.”

“The worship pastor is an absolute buffoon with his lineups. He doesn’t play his best lineups very often. And now? It’s Christmas Eve! This is playoff worship time and they’re trying to do “O Holy Night” with a B-team who generates 40% less ‘corporate sing-along’ from the church than his best lineups do!”

“That one dude sings too many songs, he’s not that good, his ‘on pitch’ rate is only 80% overall and WLP (worship leader prospectus?) gives him a failing grade at hitting high notes. The girl on piano should be singing every single song, she’s a million times better than everyone else on this team. Their ‘on pitch’ rate would sky rocket and the ‘corporate sing along’ occurrence would be 2x higher!”

“The band wastes time on cheesy, upbeat songs early when all the numbers say that ‘corporate sing-along’ and ‘hand-raising’ rates are way higher on the more epic, slow build songs they always save for the end! Build the whole set from the epic songs!”

There’s never any argument for some people about the interplay between different factors which they see reflected in a few chosen statistics. For them, if you can’t measure it, it’s probably not real or trustworthy.

How about opinionated commentary from people who deeply appreciate worship music?

“How come they don’t have a drummer more often? Don’t they know how much better the atmosphere is when there’s a drum set bringing extra power? Don't they realize that opens space for an electric guitar to soar?”

“Contemporary modern worship music is emotional, simplistic nonsense. They’d be singing more hymns if they wanted to really worship God.”

“If you go to the bigger church down the street they routinely mesh multiple songs together with big, soaring bridges and seamless transitions. This band just can’t execute the good stuff.”

As a leader of a small church, I’ve had ridiculously talented people on my team but we’re simply not the same sort of group as you see at the famous mega-churches. What’s possible and what’s desirable on a team of volunteers who live in community together outside of their interactions on the worship team are different.

I imagine the hypothetical blogboyz I’ve invented for this exercise would be as indifferent to those challenges as us sports bloggers can be when comparing college programs or different NFL franchises with their own contrasting contexts.

So what have I learned?

The easy takeaway would be “don’t talk about things you don’t know,” which is wisdom, yet there are still things we can analyze on the field of play while taking heed of the need for humility.

Analysis of what’s going on the field can actually sharpen, not decrease, if you consider some of what might be happening “under the hood.”

Since my discussion with a member of the Texas football staff years back, I’ve tried to approach my column with an aim of understanding WHY coaches make the decisions they make. It’s like a version of “steel-manning.” If you’re going to criticize something, criticize the strongest possible rationale you can conceive of rather than “straw-manning” your target by painting an unflattering representation of it.

If you can’t think of a good reason why a coach might make a particular decision, it’s possible he doesn’t have one or that he has information you can’t factor in.

We all have our opinions and there’s no fun in refusing to give them or hear others, but good faith arguments have to be a hallmark for anyone with integrity who’s been on the other side of criticism. I’m going to have fun on this blog this coming season and offer my takes, but yes it is important to consider the coach’s perspective when you’re trying to understand this game.

Grownup stuff. In recent years I've begun believing the words "with the measure you use it will be measured to you" are a real universal principal about how life works. cooperate, or don't at your own risk. Really great to see you stretch out on ideas that you can't really do in your IT work, but that are related and fit for certain readers.

One of the more interesting things about sports is how it relates to (and even enhances) other aspects of your life ! In this article, you have done that well!